A series of musings

In 1936 art historian Erwin Panofsky wrote an essay that, upon reading, revealed to me a path video games as an art form can follow to move forward from the current impediment of imitating film by instead imitating the exploitation that led to the ascension of film as a form.

It really started when I began reading Against Interpretation and Other Essays by Susan Sontag1. In her “Against Interpretation” essay from 1964 she writes,

What kind of criticism, of commentary on the arts, is desirable today? For I am not saying that works of art are ineffable, that they cannot be described or paraphrased. They can be. The question is how. What would criticism look like that would serve the work of art, not usurp its place? What is needed, first, is more attention to form in art. If excessive stress on content provokes the arrogance of interpretation, more extended and mor thorough description of form would silence. What is needed is a vocabulary—a descriptive, rather than prescriptive, vocabulary—for forms. The best criticism, and it is uncommon, is of this sort that dissolves considerations of content into those of form. On film, drama, and painting respectively, I can think of Erwin Panofsky’s essay, “Style and Medium in the Motion Pictures,” Northrop Frye’s essay “A Conspectus of Dramatic Genres,” Pierre Francastel’s essay “The Destruction of a Plastic Space.”

I began to seek out her recommendations starting with Panofsky’s “Style and Medium in the Motion Pictures,” helpfully available online through Monoskop.org. While reading I was immediately gripped with how his arguments towards the legitimization of cinema as a form could be applied towards video games.

We know video games as a form are heavily influenced and draws from film above all other forms in their creation and presentation. Games recreate scenes from the developers favorite movies and apply film grain filters to their visuals. Actors began acting out scenes on motion capture stages, and adopted the “prestige2” format of certain television trends. Unreal Engine is used to generate backgrounds for Lucasilm’s Stagecraft sets, and games are reliant upon film for nearly all of its desperate attempts to become legitimized as a form of art. This is why Roger Ebert’s original answer about his view of video games as art and subsequent follow ups continue to be bitterly referenced in conversations about the form today. So much so that a few days after first writing this paragraph Patricia Hernandez published a piece on Polygon titled, “Roger Ebert saying video games are not art is still haunting games,” which basically does all the work I was originally going to do chronicling the responses to his original writing. Thanks for saving me that time Patricia! Here was a film critic, one of the most well known by the public, putting down video games as a form. Was he wrong?

Examining the initial prompt itself, can you, “cite a game worthy of comparison with the great dramatists, poets, filmmakers, novelists and composers?” I doubt it. Much like his partner Gene Siskel and his countless “tests” for films such as the test of, “Would you rather watch the film on screen or watch documentary footage of the cast sharing a meal?” This question works as shorthand but must be elaborated on, which thankfully Ebert eventually did in his two write ups in 2010. In the first Ebert touches on two points I find most illuminating. One is that why are those who play video games so in need of validation of their play?

Bobby Fischer, Michael Jordan and Dick Butkus never said they thought their games were an art form. Nor did Shi Hua Chen, winner of the $500,000 World Series of Mah Jong in 2009. Why aren't gamers content to play their games and simply enjoy themselves? They have my blessing, not that they care. Do they require validation? In defending their gaming against parents, spouses, children, partners, co-workers or other critics, do they want to be able to look up from the screen and explain, "I'm studying a great form of art?" Then let them say it, if it makes them happy.

You see this everywhere online. Video game culture reeks of desperation to be taken seriously. This escalated when the commercial value/revenue generation of video games as an industry began to surpass other forms, such as this write up from 2009: Videogames now outperform Hollywood movies. Not that box office has ever been a reliable indicator of art-worthiness. This angle of gross revenue generation persisted as an angle with which to present the consideration of, “Please take us seriously,” in the wider culture but not to much success. Take video games seriously! Yes, they’re fun, but they matter culturally too.

Video game coverage remains mainly to the sites dedicated entirely to their existence, and increasingly to popular culture at large. This is why you will occasionally get some mainstream coverage of video games that include the perennial, “Video games, they aren’t just Pac-Man anymore.” The times you do see writing on video games in places such as The New York Times or The New Yorker and you instantly recognize that the writer understands the form of games it is from freelancers such as Yussef Cole or Jamil Jan Kochai and not a staff member. Dedicated writers, such as ones who do consistent work covering film and food, don’t exist for video games at most traditional press outlets. The Washington Post has Gene Park but also closed their video game vertical, Launcher, early this year. There are a lot of reasons why this is: the rich eating up and closing down websites, nobody wants to fund good criticism because the revenue doesn’t justify the investment, more people watch video coverage of games [YouTube or Twitch] than they do reading text, and a hostile audience to name a few. GameInformer, one of the longest running sources for video game coverage, was shut down, everyone laid off, and the entire website wiped before 9:00am PT on Friday, August 2nd in a shocking disregard for the decades of work from hundreds of individuals.

My dream for a long time, and one that occasionally persists in my daydreams of today, was that the sign that video games had really “made it,” was that The New Yorker would have a dedicated writer for games who would write about the games, the people, and the culture around them just like the magazine does for numerous other topics. This was a job I invented for myself to fulfill, one that does not exist.

The hyper focus on commercialization within conversations about video games is Ebert’s second point,

I allow [Kellee] Sangtiago the last word. Toward the end of her presentation, she shows a visual with six circles, which represent, I gather, the components now forming for her brave new world of video games as art. The circles are labeled: Development, Finance, Publishing, Marketing, Education, and Executive Management. I rest my case.

As Hernandez notes in her write up,

Perhaps, deep down, the industry is still fighting to convince itself of its worthiness. Mainstream appeal and money are not the same as respect, nor do they inherently crown their subjects as art. It is easy to evoke Ebert when The Game Awards, which aims to be gaming’s version of the Oscars, spends more time debuting trailers of upcoming video games you can pre-order than celebrating creators or their art. Some awards aren’t broadcast at all, and speeches are cut short in favor of advertising the next big thing.

So many games exist nowadays as a vacuum sniffing for money. We even have our own genre, Gacha games3, who now utilize the flashy graphical style of traditional console games in order to lure in players and be evaluated as something other than a slot machine masquerading as an action game. As Noah Caldwell-Gervais wrote for Baffler,

Games as an industry, instead of an artistic medium, don’t want that kind of success [20 million copies of Elden Ring being sold] for only the games that are worthy of it. The industry needs to make money like that on the games built without subtlety, or craft, or heart. The industry needs to pull a profit off the slop too, and there is nothing they won’t gut or sell out to do it. If the old way was to tax failure, the new way is to dilute success, to treadmill the experience such that it never reaches a destination. Just one more quarter, one more season pass. The best games are those that question their own assumptions, communicating something more than just being the game of it. Many do not, and most cannot: the money is only in the repetitions.

This is why I wrote in 2019 that, “Games are art, but frequently it is a byproduct and not the intention.” Games of the same ilk as Disco Elyisum or Pentiment are exceptions to the rule. The former existed as a brief miracle of collaboration before falling prey to the desires of capital4 and the latter existed as a low-risk investment to keep staff members around for the Next Big Thing. Both are exceedingly beautiful but also exceedingly rare to see in the field. The commercial aspect of game production is not new to any form of art, as we will see in Panofsky’s writing from 1936.

Linking back around to Panofsky, he writes in “Style and Medium in the Motion Pictures,”

It was not an artistic urge that gave rise to the discovery and gradual perfection of a new technique; it was a technical invention that gave rise to the discovery and gradual perfection of a new art.

Here is where I began to link the production of (early) filmmaking with that of video games. Games were not created out of an artistic urge but a commercial one. They existed to extract money from the pockets of adults and children, first in the arcades and now continue to do so in much more complex and insidious ways. Games are games, entertainment, a toy—a tradition Nintendo continues to play into with nearly all of their output—to be played with and enjoyed without much deeper thought or consideration.

From this we understand two fundamental facts. First, that the primordial basis of the enjoyment of moving pictures was not an objective interest in a specific subject matter, much less an aesthetic interest in the formal presentation of subject matter, but the sheer delight in the fact that things seemed to move, no matter what things they were.

You can link this delight at movement to that delight of control and interaction in video games. The simple pleasure of moving a joystick and knowing that your action created a response viewable immediately on-screen. Having a toddler showed me first hand the frustration of being handed a controller that was not actually controlling the figure moving on-screen. There was a connection being made between the joystick and the movement and when that connection was attempted to be replaced with artifice it was broken.

Not until as late as ca. 1905 was a film adaptation of Faust ventured upon (cast still "unknown," characteristically enough), and not until 1911 did Sarah Bernhardt lend her prestige to an unbelievably funny film tragedy, Queen Elizabeth of England. These films represent the first conscious attempt at transplanting the movies from the folk art level to that of "real art"; but they also bear witness to the fact that this commendable goal could not be reached in so simple a manner. It was soon realized that the imitation of a theater performance with a set stage, fixed entries and exits, and distinctly literary ambitions is the one thing the film must avoid.

Those primordial archetypes of film productions on the folk art level success or retribution, sentiment, sensation, pornography, and crude humor could blossom forth into genuine history, tragedy and romance, crime and adventure, and comedy, as soon as it was realized that they could be transfigured not by an artificial injection of literary values but by the exploitation of the unique and specific possibilities of the new medium.

It is here that we learn the most important lesson/takeaway/point that can be applied to video games: That they cannot rely on the imitation of another form and must instead exploit the unique and specific possibilities of the medium it is. For Panofsky and film it was the “close-up” that could not be matched by any other existing form,

wherever the dialogical or monological element gains temporary prominence, there appears, with the inevitability of a natural law, the "close-up." What does the close-up achieve? In showing us, in magnification, either the face of the speaker or the face of the listeners or both in alternation, the camera transforms the human physiognomy into a huge field of action where given the qualification of the performers every subtle movement of the features, almost imperceptible from a natural distance, becomes an expressive event in visible space and thereby completely integrates itself with the expressive content of the spoken word;

Panofsky also compares the co-operative making of a medieval cathedral to the collaborative nature of filmmaking,

It might be said that a film, called into being by a co-operative effort in which all contributions have the same degree of permanence, is the nearest modern equivalent of a medieval cathedral; the role of the producer corresponding, more or less, to that of the bishop or archbishop; that of the director to that of the architect in chief; that of the scenario writers to that of the scholastic advisers establishing the iconographical program; and that of the actors, camermen, cutters, sound men, make-up men and the divers technicians to that of those whose work provided the physical entity of the finished product, from the sculptors, glass painters, bronze casters, carpenters and skilled masons down to the quarry men and woodsmen. And if you speak to any one of these collaborators he will tell you, with perfect bona fides, that his is really the most important job which is quite true to the extent that it is indispensable. This comparison may seem sacrilegious, not only because there are, proportionally, fewer good films than there are good cathedrals, but also because the movies are commercial. However, if commercial art be defined as all art not primarily produced in order to gratify the creative urge of its maker but primarily intended to meet the requirements of a patron or a buying public, it must be said that noncommercial art is the exception rather than the rule, and a fairly recent and not always felicitous exception at that. While it is true that commercial art is always in danger of ending up as a prostitute, it is equally true that noncommercial art is always in danger of ending up as an old maid.

This same comparison is summoned by Roger Ebert,

But we could play all day with definitions, and find exceptions to every one. For example, I tend to think of art as usually the creation of one artist. Yet a cathedral is the work of many, and is it not art? One could think of it as countless individual works of art unified by a common purpose. Is not a tribal dance an artwork, yet the collaboration of a community? Yes, but it reflects the work of individual choreographers. Everybody didn't start dancing all at once.

There is another connection between Ebert and Panofsky and it is a mere reference in Ebert’s but the larger focus of Panofsky, the definition of art. Ebert makes a passing remark that, “Plato, via Aristotle, believed art should be defined as the imitation of nature. Seneca and Cicero essentially agreed.” When looking further into Panofsky’s works I began reading his book, “Idea: A Concept in Art Theory” from 1968 (also helpfully supplied by Monoskop.org). This book is mainly focused on charting the history of cultural interpretations and arguments for and against Plato’s views on art, be it “copying exactly” or “copying imaginatively” our “sense-perceptible reality”.

Parallel to this idea of "imitation," which included the requirement of formal and objective "correctness," art literature in the Renaissance placed the thought of "rising above nature," just as art literature had done in antiquity. On the one hand, nature could be overcome by the freely creative "phantasy" capable of altering appearances above and beyond the possibilities of natural variation and even of bringing forth completely novel creatures such as centaurs and chimeras. On the other hand, and more importantly, nature could be overcome by the artistic intellect, which-not so much by "inventing" as by selecting and improving-can, and accordingly should, make visible a beauty never completely realized in actuality. The constantly repeated admonitions to be faithful to nature are matched by the almost as forceful exhortations to choose the most beautiful from the multitude of natural objects, to avoid the misshapen, particularly in regard to proportions, and in general-here the notorious painter Demetrius is again a warning example-to strive for beauty above and beyond mere truth to nature.

This examination of the history of art theory had a very clarifying effect on a consistent problem I have with modern video game development: its insistence on chasing after verisimilitude in its rendering of graphics, visuals, the recreation of reality in an attempt to ever closer match it. This tendency has existed for much longer than games have existed, and what a fool I was for thinking this was somehow unique to video games. Throughout the history of art there have been movements and arguments about the purpose and definition of meaningful or worthwhile art. The fundamental sides, as Panofsky describes them, were “that the work of art is inferior to nature, insofar as it merely imitates nature, at best to the point of deception; and then there was the notion that the work of art is superior to nature because, improving upon the deficiencies of nature’s individual products, art independently confronts nature with a newly created image of beauty.”

Games, specifically the kind I speak on, the ones who chase “realism” in their renderings, have always been a combination of these two motives. On the one hand they desire to imitate nature, in the detail of the textures of surfaces, the sweat of individuals, the detail of their hair. And they also seek to take the most beautiful parts of nature and combine them together into something superior to that which can be found in nature. You find this most often in the amalgamations of the world within Rockstar games. Red Dead Redemption II’s world map is not an exact copy of nature but a new and superior version of America that does not exist in our reality but is made up of the most beautiful components found across it. Death Stranding consists of faces recreating recognizable actors and also displays a condensed United States made up of Icelandic features.

This does not change my dissatisfaction with this trend, and the obvious human cost it has taken these past years, as the quantity of people required to continually push the amount of detail exponentially increases each generation and the bottom line increasingly is not met due to the greed of those with money and power over the decisions who are now selling the lie of the misnomer “A.I.” which consumes and regurgitates the work already existing. What it does do is make the motivations behind this so much larger than just, “video games want to look just like the real thing/better than the real thing.” These motivations behind the creation of art have always existed and will continue.

Despite the increasing visibility of alternate video games and the diverse people making them, there is still an emphasis on escapist simulacrum in popular criticism and marketing. Studios and firms sell experiences that feel “real,” beyond the artificial worlds of games past. They may not be talking about pure polygon counts, as an embarrassing David Cage did in 2013, but they are talking about dynamic breathing, realistic kissing, rope physics, and motion capture. All things to make games better, more emotional, more thrilling. Video games vanish, kill, and stop time. Every game is a single moment, a continuous, immersive reality to be swept up in. They are more real, more able to make us escape, than ever before.

This is a bald-faced lie of capital. That lie has only become more hollow as the leap from console generation to console generation has become less dramatic and as exploitative labor practices continue to permeate the industry5.

Returning to video games and the “exploitation of the unique and specific possibilities of the new medium,” I have to first establish the failings of the current system. Video games can only do so much. Hold out your hand and manipulate your fingers back and forth, along their rotations of your fingers, wrist, elbow, arm, the fine motor movements of your entire body, be aware of that. And now view how limited video games are in replicating anything close to that amount of control and movement we can exert over not just our own body but on our surroundings, what we can reach out and touch and manipulate. Games are severely limited. This is also why I write how realism will not save us. VR has become the next jump into this type of control, of interaction and representation, but even there you see how insufficient it is and how the most marketable aspect of the recent wave of VR has become how it can act as another screen for you to watch YouTube on. A controller, even a keyboard, is limited in how deftly and minutely you can control a character in a game, and beyond that the representation of the world within that game is severely limited. You mostly just shoot things and press X whenever a more complex effect is required to be enacted upon the world.

This is another way of attacking the lies of video games, the lie of go anywhere, do anything, of the haptic feedback in your Dualsense causing actions in-game to feel even more real. As if pulling R2 on a controller will ever be able to adequately imitate the weight, force, and deafening noise of a bullet being fired from a gun. I would like to think this ineptitude is similar to what Ed Smith wrote about for Unwinnable (though I repeat it here as a condemnation),

I raise these examples not with judgment or condemnation – the point is not that this, this impermanence that seems irretrievably a part of the videogame as an artifact – is somehow in and of itself destined to make games artistically empty. The point is that games, as they have been designed, formalized and understood thus far in their history, have inconsistency embedded in their nature. The videogame, by its form, is simultaneously both completely pliant and highly volatile. When we see these smaller, intra-narrative inconsistencies – Red Dead Redemption, Far Cry, innumerate others – they are, in a sense, true to the nature of games. But what’s happened over the last 15 years is that creators of games have given up with trying to challenge or change the shapeshifting and contradictory nature of the videogame, and have instead embraced it, and in the process generated a new form of art that both reflects and helps instantiate our hopeless postmodern spiritual crisis. One of the guiding design ethics of modern videogames is to be as diffuse as possible, to allow for anything, and in the process, provide nothing by way of moral instruction or guidance. What we call player agency, creativity, exploration, the sandbox, these are all euphemisms for a meaning vacuum that videogames have become expert at creating.

Games cheat their lack of ability through cutscenes. Anytime a game requires the characters to perform actions not possible within the gameplay control system we cut to a cutscene, an imitation of a movie, to present a fluidity and harmony of movement and action that moves us forward. The most blatant example of this was the recent showcase for the Indiana Jones video game. A game controlled from first person that sees the player brawling and solving puzzles. However, once the game needed the characters to do something other than picking up blocks of bricks and items to place in a slot or punch Nazis it had to present a cutscene that contained all the choreographed set piece action you expect from an Indiana Jones movie. It could not and cannot do that within the gameplay where the player has control.

Quick time events were a sort of band aid, stop-gap for this problem. God of War is most recognized for its usage of quick time events in the form of executions of larger enemy types and its grandiose boss fights. After dealing enough damage through the traditional gameplay system of performing button combinations to perform strings of attacks and whittle health down, an enemy would pause and a giant glowing circle button prompt would appear. Get close enough and press the button and Kratos will begin to perform an elaborate sequence of animations not possible within the traditional gameplay system, requiring the player to match on-screen button prompts in a simon-says sequence of imitation in order to successfully complete the animation and execute the enemy. This animation cannot be completed by the player and the traditional method of interaction with the game. All the player can do is light attack, heavy attack, grab, use magic, and jump. They can sequence out actions together to enact more complex movements by following along the predetermined combinations you unlock more of as the game progresses along, but the action of jumping onto a minotaurs back or wrestling with its arms as you attempt to force your sword down its throat are specific to when the game prescribes it as available. Quick Time Events were an attempt to embrace the medium of the form more so than just playing a cutscene.

The simple input-response that separates video games from all other forms is mistakenly compared to a “Choose your own adventure” book, in that both video games and the genre of book follow different pre-written paths depending on the player’s choice. This comparison is fairly weak given the enormous gap in both how many minute player choices are being made, such as what skill to spend a point on or how long to linger within any given space, and the obvious difference in presentation between the visuals of a game and the plain text of a novel.

What are some examples of truly exploiting the possibilities of the medium? I can think of a few examples.

Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriot’s final act sees Solid Snake crawling through a series of hallways full of microwave radiation that both the character and player know to be fatal to him in his “Old Snake” state. The player is called upon to mash the X button continuously to enable Snake to continue crawling towards his end goal. This was a simple act, mashing a button on the controller, but the framing of it: displaying the different characters actions contemporaneously onscreen while you were crawling at the climax of the game, made it memorable despite its simplicity. Snake would not continue onwards without the player’s input. This was not a movie in which the viewer feels anxiety, such as when Aurora slowly makes her way towards the leathal touch of a spindle, but can do nothing about it. A game requires participation to move forwards.

Within the same game there are multiple “briefings” in which a cutscene plays laying out much exposition, but the player is able to control a small robot, the same robot controllable during regular gameplay, to move about the set of that cutscene and collect items or simply observe the set. The location is limited in its size but the integration of cutscene and gameplay here is unheard of. Video games allow us to occupy spaces in a way that no other medium can, so allowing that occupation and movement to occur during what is a traditional cutscene in a game full of traditional cutscenes, to the point of universal complaint/mocking, is worthwhile and sadly unique to this game from 2008.

Nier Automata is another game that exploits the medium in that in its final ending, Ending E. At the end you will be placed into a gameplay system of a top down twin stick shooter, a system you have used throughout playing the game, except now you are shooting the credits of the game. The difficulty of avoiding enemy bullets becomes increasingly harder as the credits progress and the game will frequently ask you if you are giving up after death. Defying this prompt will eventually lead to an offer of help from another player. Accepting makes the procession much easier and as you take hits other players usernames will be displayed as “[X]’s data lost.” After defeating the end credits and watching a cutscene you will be prompted to offer up your own save data in order to aid another player as they reach this ending and similarly battle the end credits. The cost is that your save data, the accumulation of all your decisions and time during the course of the game to this point, will be deleted. If you accept, the game goes through the menu and systematically erases all maps, quests, items, weapons, skills, intel, and system data. It is perhaps the ultimate sacrifice a player can make: the erasure of all their time and accomplishments from the past 30 plus hours.

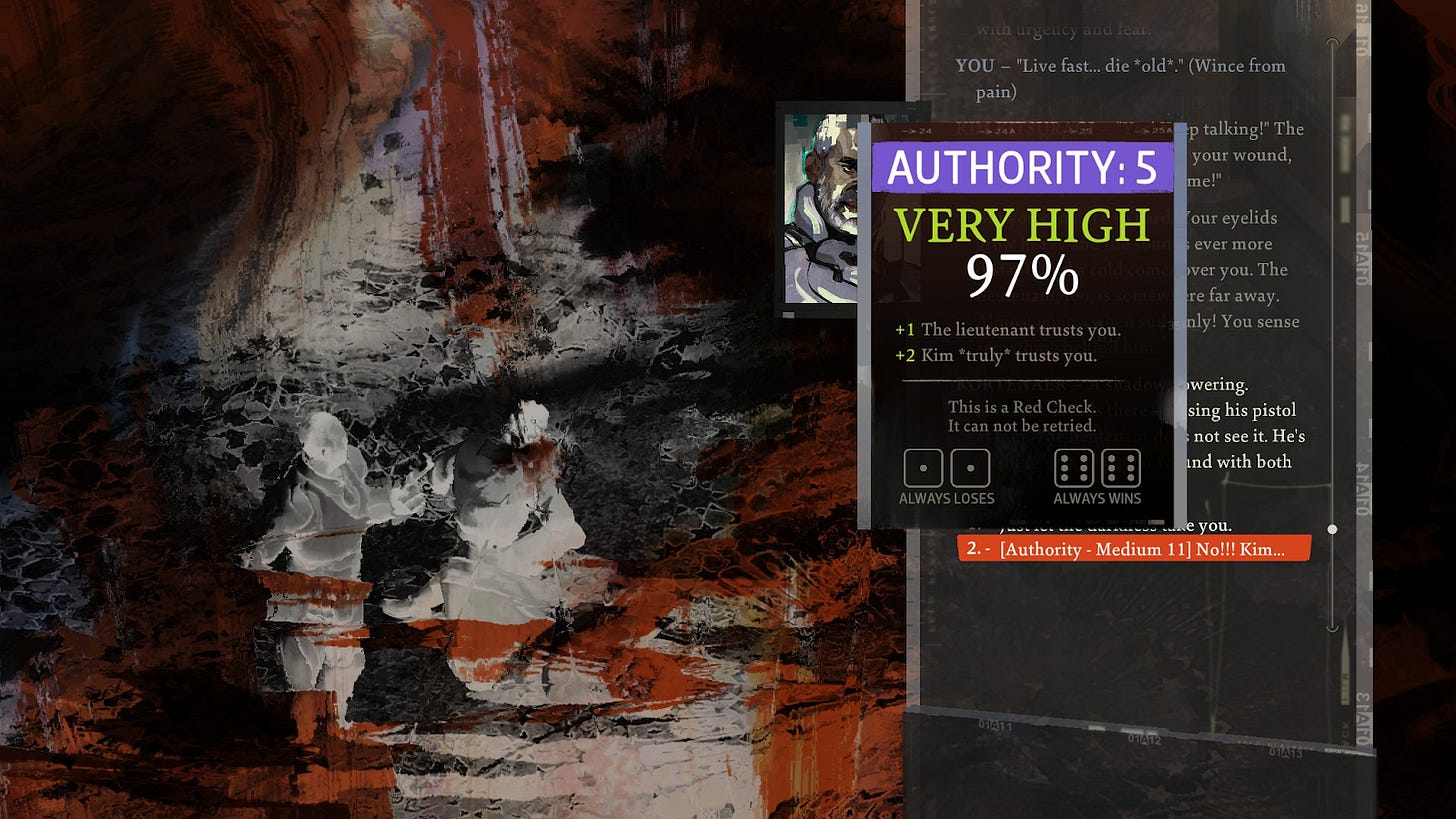

A majority of your time within Disco Elysium will be spent reading. While I do give credit that the form of text allows for a greater depth and variety of imagery and ideas than drawing—by which I mean a text can be both a much simpler way to draw a picture in one's mind and is much richer and unique compared to actually having to actually draw—there is also the constant dice rolls being made behind the scenes and in plain sight that determine exactly what text a player will be served in addition to the main plot. The plainest and simplest explanation of what makes video games video games is that the player makes inputs and the game reacts with visual changes on-screen. In Disco Elysium the player makes dialogue choices of what to say in conversations and picks what skills to invest points into in order to make succeeding checks for that specific skill more likely to occur. The culmination of all of these decisions and investments occurs during the tribunal scene in which you engage in the one and only shootout of the game alongside your partner, Lieutenant Kim Kitsuragi.

Kim is perhaps the greatest example of Haecceity, or “thisness,” which I learned through James Wood’s “How Fiction Works.” Disco Elysium is full of flourishes of haecceity, what Wood describes as, “any detail that draws abstraction toward itself and seems to kill that abstraction with a puff of palpability, any detail that centers our attention with its concretion.” Kim allows very little detail about himself to slip through during the course of your investigation but each description of his pride over his vehicle and his feelings towards his previous partnership go a long way to establishing his substance in character. These moments are also often drawn up through the voice each skill is given. Your skills are not only numerical buffers to the dice rolls but active voices inside your head whose short additions and descriptions are the source of a majority of the haecceity within Disco Elysium, most notably the Shivers skill which can at one point inform us that the entire neighborhood the game takes place in will one day be wiped away by an atomic weapon. This only appears depending on both a dice roll and helped by your allotment of points.

Most video games operate under the presumption that even if every player is being served the same predetermined narrative, there will still be some flexible room for a player to express themselves in the options available to them, one of the most marketable being “choices and consequences.” Oftentimes this is a lie, such as Telltale’s The Walking Dead from 2012 which set itself up to disappoint by loudly announcing to the player that their choices would have consequences, vastly overselling exactly how (in)consequential the decisions would be. Dragon Age: Origins, and Bioware at large, was marketed on the basis of the variety of decisions and reactions available. However my investigation into this potential has so far been a disappointment. Disco Elysium does not market itself as a choose your own adventure with multiple endings. Instead it asks, “What kind of cop are you going to be?” However the game does contain one of the most powerful consequences during the tribunal dice rolls. Your partner Kim Kitsuragi is treating your gunshot wound and a mercenary appears behind him. This check is not only based on your authority score but it also buffeted by the culmination of smaller minute decisions made that affected your relationship with Kim, which add six words of immense consequence to the game.

Pentiment brings to mind a topic I want to pursue further at another time when I’ve dedicated more reading on the subject: the push and pull of player and character within video games. Many video games allow the player to pick and choose what dialogue the player character will say during a conversation. There is a wide swath of options and flexibility to this. Some games have the player pick every single dialogue option, others will only allow the player to pick at specific pre-chosen times. Pentiment is the latter, which is the more interesting option to study.

In this form there exists two characters: the first is the player who makes choices on what the character is going to say, and the second is the character who speaks for themselves without any player input. This character exists within this world within a predetermined set of defined traits, attitudes, beliefs, but are bendable just slightly to the player’s whims as well. Sometimes the character will respond without the player’s input, other times the player will determine what is to be said. It is a push and pull between the developer who created and defined the character, and the player who is given free reign to make choices, the consequences of which also vary game to game. Sometimes you will have a game such as the aforementioned The Walking Dead which lies to the player about their choices mattering because the entire story is predetermined and the player’s choices do not alter the course of the plot but instead allow the player to fill in portions of the character: make them an asshole or an honest person. It is quite boring to engage with this, and offensive when the game itself profoundly states that your choices will matter only to always lead to the same conclusion. Pentiment mostly avoids this by not sign posting when consequential decisions are made, and also not throwing it in the player’s face that their “decisions have consequences” when the majority of the plot procession is immovable.

The most pivotal usage of this gameplay system is during the climax of the second act. Andreas has been working to solve another murder, this time out of an obligation to justice due to his presence with the accused during the time of the murder. It’s a beautiful little flair that the person you absolutely know is innocent of the crime is also a massive piece of shit. Andreas is older than the first act, and now has a protege accompanying him on his travels and now murder investigation. Throughout the act you are given opportunities to impart advice and show care for Caspar. The twist is that the “skill check” that determines Caspar’s fate is for whether or not you showed care for Caspar throughout your investigation. It’s a major gut punch because the player is inclined to treat Caspar well, out of both a general moral goodness a majority of players pick when given good/evil paths in video games and also out of compassion for Andreas who sees in Caspar a sort of son-figure-replacement for the son he lost the plague prior to the events of this act. Your reward for showing care is not his salvation; your caring leads him to his death. This is a direct consequence of the player’s choice, a possibility only permitted by the form that is video games.

Sontag also wrote in “Against Interpretation” that, “…films for a long time were just movies; in other words, that they were understood to be part of mass, as opposed to high, culture, and were left alone by most people with minds.” Despite my hope that the examples listed will become more recurring, I no longer believe video games will ever transcend “from the folk art level to that of ‘real art.’” We are in too deep. The form has matured in such a way for so long that reversing course is impossible. The financial investment behind the creation of the largest, most marketed games is for more battle passes, more monetization, more slot machines. Games, as a form, at the most marketed, purchased, and mass cultural level are already happily exploiting not the uniqueness of the form but the labor behind it and profitability of its players. You look at the past five years of best sellers and a majority of them exist alongside coins6, points7, credits8, V-bucks9, shards10, Caliber11, Helix credits12, BFC13, Platinum14, Cash15, Tokens16, Krystals17, Tickets18, Robux19, and Riot Points20.

Newzoo’s report (via GameDiscoverCo) from April shows that as time goes on, players are spending more and more time with older titles (Fortnite, Roblox, League of Legends, Minecraft, and Grand Theft Auto V (aka Online)) and new releases are suffering due to this. As GameDiscoverCo puts it:

The issue remains: catalog revenue is strong, big old games get played continually, but the gap for new games to be bought and played is smaller than the amount of money going into that hole, by a lot. But obviously, new games are where most of the investment is going.

This is going to be a permanent problem and significantly affect employment levels and success in the game biz - particularly because there's a lot more games out there in the market than there used to be.

Investment in new games are going towards reheated slop and even the established developers and brands are suffering due to circumstances beyond the control of those being laid off. I am conscious more than ever that the mindset that things now are worse than they have ever been has been a constant throughout time, but it certainly does not seem like things are going to get better anytime soon, extending that even beyond the vapid interest of a video game critic. I love Disco Elysium eternally for capturing, above all of its other accomplishments, the feeling that the revolution has failed, that the chance at material change has passed beyond us, and our future is one of rotting21.

Grace Benfell and Soph recently had a Closet Crit episode on this very essay on their Patreon which is well worth the listen and support.

USGamer.net is gone and its URL indicates, “The best of the USgamer team’s content has been archived on VG247.” yet this piece, “Move Over Prestige TV, God of War and Other Prestige Games are Taking Over Now” by Caty McCarthy, which is one of the earliest recognitions of this widely accepted trend, is not! Why are we so bad at preserving good writing! Also looking at you KillScreen! Grab DED LED if you haven’t already!

They even have their own subreddit, “We celebrate gacha games.” and get games media to go from writing articles about gacha games to working for gacha games, or as @_girltype put it, “the way gambling has just saturated video games now is so fuckin dark. if you whale enough at the virtual casino they'll even let you serve the drinks now!”

I also occasionally think of Julie Muncy’s observation: “it sucks, and i wish them all the best, but i can't stop thinking that the dev collective behind disco elysium falling apart in classic non-heirarchal leftist org fashion is, like, dante-level black irony”

Grace Benfell, “Final Fantasy’s Meta-Narrative Proves Video Games’ Short Memory”, Into the Spine

I have extended the listing of game currencies to show the breadth of them. This isn’t exhaustive just the ones I believe are relevant: Apex Legends, Rust, Rage 2, Tekken 8, Conan Exiles, Pinball FX, Overwatch 2, Ghost Recon Breakpoint, Street Fighter 6, Metal Gear Survive, LEGO 2K Drive

Valorant, UFC, Mass Effect Andromeda, Uncharted 4, NHL, Need for Speed, Destruction AllStars, NBA Live, Call of Duty: Vanguard, Madden, Call of Duty: WWII, Call of Duty: Modern Warfare, FIFA/FC, Call of Duty: Infinite Warfare, Call of Duty: Modern Warfare II, Call of Duty: Modern Warfare III, Call of Duty: Warzone, Call of Duty: Modern Warfare Remastered

Far Cry 6, Tom Clancy’s The Division 2

Fortnite

Anthem (lol), Apex Legends (again)

The First Descendant

Assassin’s Creed Valhalla

Battlefield 2042

Diablo IV

Grand Theft Auto Online, DC Universe Online, Planetside 2

Minecraft, Overwatch League (this got shut down???), Disney Speedstorm, Dragon Ball: The Breakers, Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora

Mortal Kombat 1

Resident Evil 4

Roblox

League of Legends

I apologize for ending on such a downer. Next time: What was going on in that Tomb Raider reboot anyway? Or: What is it about these checklist games that draw us to them?